WHO NTDs Roadmap 2021-2030

The WHO Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs) Roadmap 2021-2030 was launched at the end of January after a long period of international consultation. There is an abbreviated version of the Roadmap, but we recommend the full version as well as the NTD Sustainability Framework, a companion document.

The Roadmap is exceptionally important for leprosy. The major themes, especially the cross-cutting approaches of integration, mainstreaming, country ownership and sustainability, form a new landscape for ILEP’s strategies and activities. The Roadmap also has four detailed pages of specific objectives and approaches for leprosy, which form the basis for the new WHO Global Leprosy Strategy, due to be launched in March.

Accelerate programmatic action

This is the first of the major themes in the Roadmap. There is an emphasis on the need for research and development into new interventions and new tools. For leprosy, three critical actions are listed:

- Update country guidelines to include use of single-dose rifampicin for postexposure prophylaxis for contacts, and advance research on new preventive approaches.

- Continue investment into research for diagnostics for disease and infection, and develop surveillance strategies, systems and guidelines for case-finding and treatment.

- Ensure medicines supply, including access to MDT, prophylactic drugs, second-line treatments and medicines to treat reactions; monitor adverse events and resistance.

Intensify cross-cutting approaches

This is the second major theme. The Roadmap promotes a shift is from a siloed disease-specific approach to cross-cutting approaches, including integration across multiple NTDs, mainstreaming in national health systems, and coordination with other sectors within and beyond health.

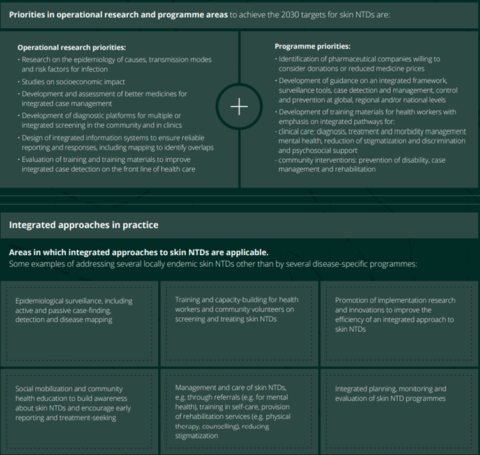

For leprosy, one fundamental issue is integration. The Roadmap encourages countries to integrate all NTDs on to a single platform that includes not only prevention but also treatment, care, rehabilitation and health education. There is a particular emphasis on integrating the eight skin NTDs: Buruli ulcer, leishmaniasis, leprosy, LF, mycetoma etc, onchocerciasis, scabies and yaws. One of the indicators in the Roadmap is the number of countries that implement integrated skin NTD strategies (currently 4, but the target is 40) so it can be assumed that leprosy-endemic countries will be urged by WHO to consider this. Figure 1 below shows some of the ways in which WHO expects that leprosy services will be integrated with other skin NTDs.

Figure 1

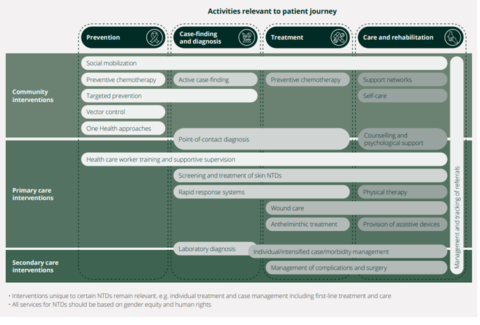

Mainstreaming in national health systems is another feature that is relevant in situations where leprosy programmes are implemented separately, or in parallel, with the country’s mainstream health system. The Roadmap is clear that NTD interventions, from prevention to diagnosis, treatment, care and rehabilitation, should be delivered through community, primary or secondary care facilities in the national health system. This contributes to sustainable, efficient NTD prevention and control and – in line with universal health coverage – it enables NTD patients to access all aspects of treatment, care and support. In many countries, health systems strengthening will be essential, otherwise the risk is that mainstreaming reduces patients’ access to leprosy and other NTD services. Figure 2 below describes how this mainstreaming could work in practice, though details would differ from country to country.

Figure 2

There is also emphasis on coordination with other departments in the Ministry of Health, and other sectors beyond it. For leprosy, some of the obvious intersections within Health are mental health, disability and inclusion, and eye health. There are other coordination opportunities beyond Health, including WASH, education, and justice and social welfare (particularly important for preventing structural discrimination including abolition of discriminatory laws, and working with communities to conduct anti-stigma interventions).

Country ownership

The third major theme is a shift is from an agenda driven by partner support and donor funding, to country ownership and (primarily) domestic financing. The sustainability framework is an important document in this regard, because it describes the crucial ongoing role of INGOs like ILEP in a context of country ownership.

The framework defines sustainability as ‘the ability of national health systems to maintain or increase effective coverage of interventions against NTDs to achieve the outcomes, targets and milestones identified in the new road map for 2030.’ To build sustainability, not only will NTD programmes need to be built upon national health systems, but also international donors and implementing partners will need to consider their potential roles in sustainability and especially in strengthening health systems. When countries depend on partners for NTD-specific expertise and funding, there is a risk of fragmentation, usually inadequate focus on health systems strengthening, and chronic uncertainty over whether partner funding will continue. The framework also raises the issue of power: who decides how NTD interventions are organised and implemented?

Partners like ILEP and its member associations are urged to use the framework to think through some of the deeper issues on sustainability. In particular, we are encouraged to identify opportunities in which technical assistance and funding assistance can be used, and possibly redirected, to better support sustainability.