Open Letter to President Emmanuel Macron

Open letter to President Macron of France, organised by an informal, global network of people affected by leprosy.

Dear Mr. President,

As women and men who have experienced Hansen’s disease, more commonly known as leprosy, we were disheartened to read international media reports earlier this month that quote you as calling on Europe to fight nationalist ¨leprosy¨[1]. Other national and international leaders have used similar language in high profile speeches over the past few months.

While it might be good at grabbing headlines, the use of ‘leprosy’ as a negative metaphor has consequences far beyond the political realm, because it perpetuates old and outdated stereotypes and reinforces stigma and discrimination against us, people affected by leprosy.

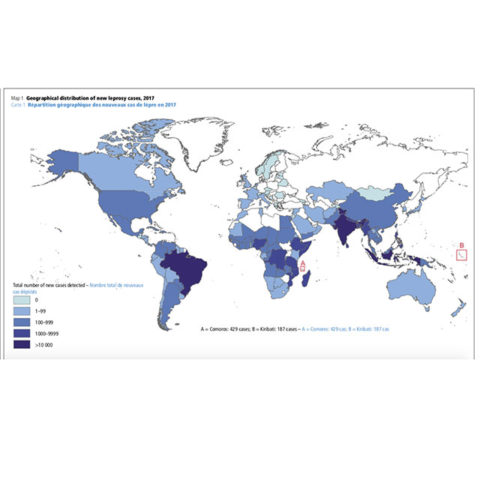

Leprosy is not a disease of the past. More than 200,000 people are diagnosed each year with leprosy, and there are believed to be more than two million people affected by leprosy who are undiagnosed and untreated. The negative social attitudes towards people with leprosy create a barrier to treatment, and hinder efforts to stop the transmission of the disease globally.

Leprosy is a curable disease. However, women and men affected by this disease are still marginalized and excluded in many places around the globe. We ourselves have experienced being isolated by family and friends, fired from jobs, discriminated and insulted by people and many other violations of our human rights. That’s why we are working hard every day to change this reality in every community.

Women and men affected by leprosy are people with hopes and dreams like everyone else. Most people affected just dream of a normal life: A place to live and work peacefully, surrounded by their family and friends. They do not want to be defined by their disease.

It is fundamental to ensure that the word leprosy is always used without the burden of stigma. Some countries already took the initiative to change the name of the disease. However, while such change does not take place all over the world, public figures and authorities have the duty to be careful with the thousands of persons affected and the millions that had their lives impacted by this disease worldwide.

We therefore respectfully ask you to not use leprosy as a negative metaphor, and to instead support people in France, Europe and around the globe fighting to stop discrimination against people affected by leprosy.

We are nevertheless convinced that this form of discrimination against us was not the objective of your statement. Yet that’s the effect it has had on us. Confident in your good will, a few of us would be very happy and honored to meet you and discuss more

In the name of women, children and men affected by leprosy around the globe,

Organizations and groups of people affected by leprosy:

HANDA (China)

IDEA Nepal

PERMATA (Indonesia)

Sam Utthan Apal Bihar (India)

FELEHANSEN (Colombia)

HEAL Disability Initiative (Nigeria)

IDEA Ghana

Morhan (Brasil)

Purple Hope initiative (Nigeria)

IDEA Nigeria

ENAPAL (Ethiopia)

APAL (India)

Comunidad de Apoyo (Paraguay)

ILEP Panel of Women and Men affected by Leprosy

Global Leprosy Champions

IDEA INTERNATIONAL

Women and men affected by leprosy:

Evelyne Leandro

Lilibeth Nwakaego Evarestus

Rachna Kumari

Jayashree P Kunju

L H Subodha Galahitiyawa

Amar Timalsina

José Ramirez

Mathias Duck

Mohan Arikonda

Ganesh Muthusamy

Sathya Arikonda

Linda Lehman

Braj Kishor Prasad

Sanjay Kumar

Anand Raj

Lucrecia Vazquez

Mainas Ayuba

Kofi Nyarko

Paula Brandao

Suresh Dhongde

Yurani Granada Lopez

Sofia Castañeda

Isaias Dussan

Felicita Bogado

Jimoh Hammed

[1] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/nov/17/emmanuel-macron-ploughs-lonely-furrow-nationalism-authoritarian-regimes; https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/macron-warns-nationalist-leprosy-threatens-europe-n931211; https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/08/world/europe/macron-nationalism-populism-wwi-armistice.html; https://www.thelocal.fr/20181101/frances-macron-warns-europe-of-a-return-to-1930s.