WHO Global Leprosy Update for 2020

The ILEP Technical Commission (ITC) has produced a commentary on the recently published Global Leprosy Update for 2020. (WHO, Weekly Epidemiological Record, 2021; 96: 421-444). The authors are Paul Saunderson (ITC), Joseph Chukwu (ITC) and Tom Hambridge (Dept of Public Health, Erasmus MC).

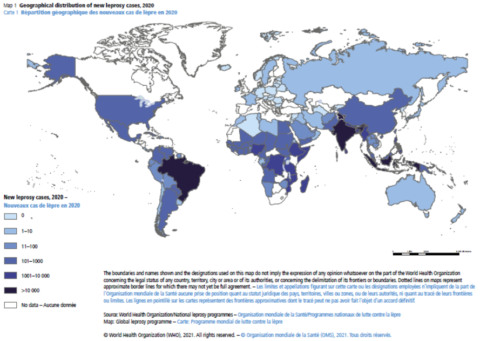

Overview

The most obvious feature is the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic and the consequent reduction in field work, including leprosy case finding and clinic attendance, in most parts of the world. Reported case numbers are generally reduced by about one third from the previous year. This is highlighted by the steep decline in new cases (and registered prevalence) compared to 2019, particularly in the three countries with the highest endemicity: Brazil, India and Indonesia. In fact, the proportion of new cases coming from these three countries remained more or less the same despite the global decline, contributing to 74% of all new leprosy cases in 2020 vs. 79% in 2019.

In total, 127 (80%) of the 160 countries reporting in the previous year provided data for 2020, but the missing data are mainly in countries with little leprosy; the submission of reports from as many as 80% of endemic countries, including all 23 high priority countries, suggests that the web-based reporting system, linked in many cases to the DHIS2 platform, has performed well in the face of the pandemic and speaks to the efficiency and promise of digital solutions in public health, even in resource-poor settings around the world.

Other correspondence has indicated similar drops, of around one third, in routine case work in various fields, such as laboratory testing for TB in Europe, yellow fever notifications in Africa, and leishmaniasis case detection globally.

As is briefly described on page 423 of the Update, we should look at 2019 and 2020 as a threshold separating two distinct epidemiological periods for leprosy, given the nature of case detection and the interruption caused by the global pandemic. COVID-19 measures that took priority in recent months, are expected to continue in many countries in the coming years, and there are also renewed efforts towards ending the transmission of leprosy being promoted as part of the new Global Strategy (2021-2030), suggesting that we may never return to the status quo ante.

Priority countries

Tables 3 and 4 present trends in the 23 priority countries. New case detection (Table 3) dropped in most countries, although DRC, Kiribati, Madagascar, Somalia and Sudan showed modest rises. All of the priority countries showing modest rises (aside from Kiribati) were in Africa, which perhaps had a later onset of the pandemic and thus less COVID-19 control measures in operation throughout 2020. As there may have been more disruption from COVID-19 in the first half of 2021 in many endemic countries, the declining trend is likely to continue, but could be mitigated by a gradual return to more normal activities going forward.

New cases reported in Brazil declined by 35%, in India by 43% and in Indonesia by 36% from the 2019 figures. The numbers of new cases with Grade 2 disability (G2D, Table 4) showed almost exactly the same trends, as may be expected. Angola showed a surprisingly large drop in new cases with G2D. A minor point is that data for Nigeria are incompletely reported, although the missing information was apparently submitted: New child cases: 87 (MB) + 10 (PB) – total 97 cases; New child cases with G2D: 15 cases; New cases with G2D: 170; Foreign born cases: 11; MB treatment completion: 90.9%; PB treatment completion: 93.4%.

Treatment completion rates: In contrast to the sharp drops in case detection/notification in 2020, it is heartening to note from the report that ‘the rates of completion of treatment for multibacillary (MB) and paucibacillary(PB) leprosy were similar to those in 2019’, averaging about 88% for MB and 95% for PB. This could be explained in part by special measures put in place by ILEP members and programme managers in some countries, to help patients continue treatment during lockdown and periods of restricted movement. The idea was, ‘if we cannot go out to detect new cases, we can at least ensure that patients already on treatment remain adherent’. Digital technology (phone calls, SMS and WhatsApp) was deployed to great effect in aid of this endeavour.

Drug-resistant leprosy: page 430 of the Update has a brief paragraph on leprosy drug resistance (AMR), tested in the 16 countries listed in a footnote, of which 6 reported the presence of AMR; Somalia is the only country in AFR on the list. Resistance monitoring should be encouraged in other high endemic areas in AFR, particularly Ethiopia, Mozambique and DRC. Indonesia has implemented leprosy chemoprophylaxis campaigns using SDR-PEP, with no report of resistance to any drugs. Altogether, 67 patients (including 13 new cases) harboured multi-drug resistant strains. This highlights the importance of drug-resistance testing as recommended in the new WHO leprosy (Hansen’s disease) strategy. This takes on added significance with increased coverage of single-dose-rifampicin prophylaxis especially in high burden countries. More detailed information about the AMR testing that is done would be valuable.

Discriminatory laws against persons affected by leprosy: Seven countries reported laws discriminating against persons affected by leprosy in their statutes. This is unacceptable in the 21st century. All are enjoined to work to repeal such laws and indeed report any discriminatory practices against persons affected by leprosy and their families to the UN Special Rapporteur on the Elimination of Discrimination against Persons Affected by Leprosy and their Family Members, or the relevant authorities in the country.

Return to normal activities

ILEP members should be encouraged to help national programs to return to normal activities, with an expected backlog of cases who were not diagnosed in the last 12-18 months. This could be done through coordinated screening of contacts of registered leprosy patients currently receiving MDT, particularly household contacts, and also by directing short term resources towards training of groups such as local volunteers and health extension workers. If implemented successfully in high endemic areas, the backlog should be manageable for field teams to address and we would expect to see a slight peak in overall incidence over the next 3 years from cases who went undetected during periods of health service disruption.

MDT supply should be monitored carefully. In theory, stocks should be adequate if less has been used in the last 12 months, but countries should order new supplies based on 2019 case numbers. Many recently supplied batches of MDT have expiry dates later than Dec. 2023, so will be available for additional new cases during the next 2 years. Nitrosamine impurities in the rifampicin supply caused some disruption towards the end of 2020, but this has now been resolved.

Conclusion

Global health services have been severely tested by the COVID-19 pandemic, both in terms of the additional burden of managing COVID patients and the disruption of almost all other services to some extent. Leprosy has been no exception. Leprosy programs have generally been able to provide ‘essential and critical services’, but routine field work was often not possible in some places for some periods. It is to be hoped that routine activities can be resumed quickly, with increased vigour.